On my first art residency at Mungo, I met artist S.O., a Wangaaypuwan/Ngyiampaa woman. We shared many conversations about our families' backgrounds, places where we had grown up, and it made me contemplate what place I belong. I spent most of my days of the residency in the old homestead with S.O. as she loved cooking and a clean kitchen just as much as I did. There were lots of cups of tea while we played with paint.

Our homestead was in a remote location in the World Heritage area. Surprising for this arid area, it rained heavily, the red clay roads were closed, leaving us flooded in for several weeks. As the days continued, I came to understand that S.O. felt uncomfortable about being at Mungo and going out for walks outside the homestead area, out on country. Since our arrival to Mungo, she had not met with any of the communities of the Willandra Lakes Region. The red roads became dark, slippery clay, and we were flooded in and trapped for some weeks. That uncomfortable feeling that S.O. exposed was probably one of my first real understanding of a 'welcome to country' and the significance of the term 'connection to country'.

I also felt unsettled in this place as I adjusted to the new surroundings and the other artists on the residency. When I left my home in Sydney, I had the strangest feeling that I could not shake. By the time I had reached Mungo, I was experiencing uncontrollable nose bleeds, and they continued for the duration of the residency. It was not your average hit in the face nosebleed but profuse bleeding that randomly occurred. My body became depleted and exhausted. There was so much red, red blood.

My superstitious Greek upbringing wondered if it was a sign.

On the last day of our month-long stay, S.O. walked with me. We found the other artists all drawing, painting, and immersing themselves in the harsh beauty of the Willandra Lakes Region. I carried my mug of tea with its knitted cosy around it of the Aboriginal flag gifted to me by S.O. when I first arrived at Mungo. It is not my flag, but I understood the weight of the gesture. I feel pretty awkward about flags. I have never felt that I belonged to any flag. I am not sure if it is a post-migrant thing or if it's a position that I have developed as I associate war and battles with flags, but this flag that S.O. gave me of the banal object to keep my tea warm linked her identity and the place where we stood together.

I started to understand why I was in Mungo and why I would need to return. So many of my questions about colour could be answered there.

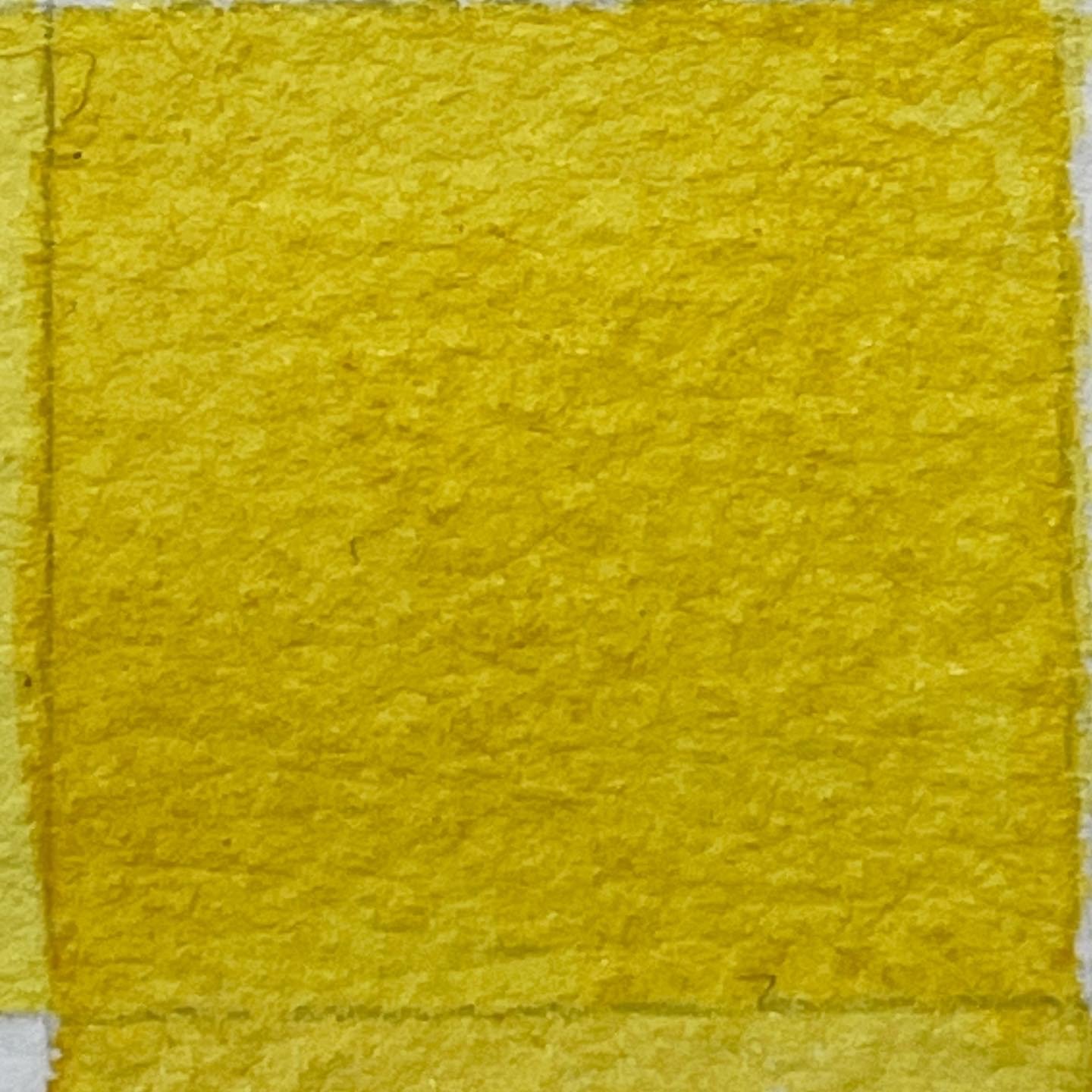

The cues for selecting a palette for this place were interconnected to this flag. The triad palette of the traditional owners of this country... the very first palette of colours. It was explained that red is the men's colour, yellow is the women's colour, and black is the sky. Now that I reflect on this, I see it is the colour of the sky at night and by day is blue. So, holding the mug cosy with its triad palette, I was reminded that Aboriginal people have painted in this country forever ago. Long before Sir Joseph Banks invaded this place, with his English box of engineered colours, to paint the rainbows of Newton. And long before the pursuit of George Field to develop a perfect triad system, this place has provided its people with the perfect triad palette. This place holds the truth of the nature of colour.

– A diary reflection on a return visit to Mungo in October 2020 after the first COVID lockdown.

“If we possessed the three colours in absolute absolute. or correlative perfection in pigments, such alone would be sufficient to compose all other hues and shades”

Like many schools worldwide, those in Australia teach colour theory through an inherited colour wheel system. At some point, in a child's art education, they learn about the application of the three primary colours and how, when mixed alongside each other, they create secondary colours. The mixtures are as follows: red + yellow = orange; red + blue = purple; and yellow + blue = green. In my years of teaching Visual Arts, I have rarely seen an art program that explicitly mentions where this practice originates, but I have seen how student artists struggle to create that perfect colour mix and balance around the wheel, if they did not choose the right primary mix of colours in the first place.

’Despite the myriad of colours available to artists today, there is still a pervading Brewsterian[i] idea that reducing the number of colours to three primary colours would produce the colours in a rainbow and further the expansive outcome of colour mixes. Field describes 'colouring' in Chapter One of his Chromatography (1835) as ‘the first requisite of painting’ (Field, 1835, p. vi). He writes that when applied in painting it, is ‘the one thing imparting warmth and life’ and that colouring is ‘the chief quality engaging attention’. He poetically describes the colour as ‘equally diffused as light, spreading itself over the entire face of nature, and clothing the whole world with beauty’ (1835, p. 57). Field’s teachings on colour, and more specifically on the primary, secondary, and tertiary mixtures, has held sway in classrooms and art studios from the early nineteenth century right up until today.

[i] David Brewster (1781-1868) was a colour theorist who expelled the ideas of the primaries (red, yellow and blue). Field experimented with Brewster's idea and extended this to secondary and tertiary mixtures.